The Tracy System of Kenpo

Jiu-Jitsu IS self-defense—it is not a

sport. It is not simply a plaything like

the martial arts of too many systems and styles that cannot actually be used in reality

when you really need it—when your life is in danger.

The Tracy System of Kenpo

Jiu-Jitsu IS self-defense—it is not a

sport. It is not simply a plaything like

the martial arts of too many systems and styles that cannot actually be used in reality

when you really need it—when your life is in danger.

Since the beginning of time, unarmed fighting has for most

of the Western World been little more than rough and tumble brawling.

In the 19th century the Marquise of Queensberry introduced

some civility into spectator fighting, and gave rise to professional

boxing.

But few men, and virtually no women learned how to “Box.”

Savate was cultivated as French foot-fighting when, as tradition holds,

French sailors observed Chinese “Boxers.”

The Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1900, and America’s Gunboat Diplomacy put

American servicemen in contact, and often fights, with Oriental forms of unarmed

fighting. Jiu-Jitsu (Ju-Jitsu) and

Judo became popular when

Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, the 26th U.S.

President, learned Judo giving

Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo, the

international acceptance Judo needed. But

Judo and Jiu-Jitsu practitioners were few in number.

This influence, however, gave rise to the military form of hand-to-hand

combat called “Combat Judo.”

Karate first appeared in America in the early 1930’s but

it was relatively unknown until American servicemen began returning from the

occupied post-war Japan. Then with

the advent of the Korean War, hundreds of thousands of soldiers were sent to

Japan as support troops. Most of

these servicemen learned Karate, because McArthur forbid Judo, but not Karate.

But the fighting style of the western world was still a "style without

style"—rough and tumble brawling. One

need only look at the movies of the early 20th century to see how the

western world fought. Fighting in

films was a shadowy mirror of how people acted and fought.

Ju-jitsu had developed as a Japanese combat martial art

over many centuries of use in actual warfare and gave birth to Judo, which was a

much more gentle way. These arts

were superb forms of self-defense in Japan.

But Judo was virtually useless against a trained Boxer, as many Judo

instructors discovered when American Boxers would challenge them.

Almost every American who trained in Judo in the ten years after WWII

would tell a story of how he had grabbed an attacker by the coat lapel to throw

him, only to find himself getting hit as he held a torn, empty coat in his hand.

Japanese Karate was not much better.

It was still, linear, and direct. It

worked well against the untrained, but Boxers and street fighters found it

useless against them. There were

many contests between Boxers and Karate men in Japan and Korea after the war.

The Karate-ka was allowed to use his hands and feet, without gloves,

while the boxer wore gloves and followed boxing rules.

Even despite these obvious disparities, the boxer almost always won.

When the boxer was allowed to fight without gloves, the match seldom

lasted beyond 30 seconds.

Judo

versus Boxing matches often produced the same results.

However, in those matches, the Boxer was not only required to wear

gloves, but also a heavy Judo Gi. “Judo”

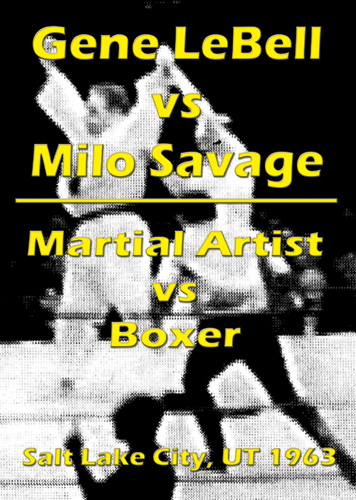

Gene LeBell is the only person who ever legitimately beat a boxer in such a

match in 1963. Gene, however, was an

exceptional man, a professional wrestler, an expert martial artist, and it was

not to his disadvantage that he was over 6 feet tall and weighed over 220

pounds.

Judo

versus Boxing matches often produced the same results.

However, in those matches, the Boxer was not only required to wear

gloves, but also a heavy Judo Gi. “Judo”

Gene LeBell is the only person who ever legitimately beat a boxer in such a

match in 1963. Gene, however, was an

exceptional man, a professional wrestler, an expert martial artist, and it was

not to his disadvantage that he was over 6 feet tall and weighed over 220

pounds.

Jiu-Jitsu versus Boxer matches were quite another thing, as

the Jiu-Jitsu fighter would simply shoot-in in a low stance, taking the first

punch to his back as he grabbed the legs and took the helpless Boxer down to

choke him out.

It is little wonder then that the Kenpo Jiu-Jitsu, which

Hawaiian-born, Japanese-raised James Mitose of the Yoshida Clan, began teaching

shortly after WWII was so effective as a form of self-defense.

Even though Mitose’s style of Kenpo had been handed down in his family

for over 700 years in Japan, it had originated in China, where “Boxing” and

kicking together were accepted forms of fighting. It is the preservation

of this art that sets Tracy's Kenpo apart from all other forms of Kenpo.

Kenpo Jiu-Jitsu is an art created by ancient Samurai Warriors of Japan, to deal with the most severe self-defense situations. It is the only self-defense art taught today that is designed to protect the individual by any and all means necessary.

Kenpo, by its powerful philosophy and devastating hand techniques, enables the individual to use enough force necessary to dissuade, disable, injure, or neutralize the assailant.

Many styles and many terms synonymous with martial arts

and specifically Kenpo exist today. While

the word Karate is a more modern term, with actually two different

meanings, Kung Fu and even Kickboxing are also terms used to describe this

fascinating method of oriental self-defense.

However, all of these styles are considered oriental forms of

boxing (striking), whereas Jiu-jitsu, Judo, Aikido, and T’ai-chi

ch’uan are oriental methods of wrestling (grappling).

Practitioners of Kenpo Jiu-Jitsu are enthusiastic

adherents of combinations of punches, strikes and kicks, blended with

throws, holds, takedowns and other compliance techniques.

Unlike most systems their training goes beyond the “one block,

one punch” theory. Working

on combinations of five or more movements, they contemplate probable

counters that may thwart their opponent’s efforts.

This realistic approach eradicates thoughts of underestimating an

opponent’s ability to take punishment or overestimating their own

ability. They learn practical

and effective movements that can have immediate effect and are not just

untried theories on paper. They

also learn that combinations can be changed instantly to fit a specific

situation and do not necessarily have to follow a set pattern.

Chances of panic in a real crisis are considerably lessened because

they are taught how to cope with our modern day methods of fighting

realistically, logically, systematically and effectively.

Training—Instruction

At Tracy’s Kenpo Studios, all beginners are given

instruction in basic stances, blocks, punches, kicks, throws, joint-locks,

chokes and takedowns.

Everyone enrolled is classified as a novice regardless of previous

training; and must therefore spend approximately three months in the

beginner class. As the student progresses, they are taught various techniques

including defenses against grabs, punches and kicks. They learn the location of vital points on the body and

how to use their natural weapons to their maximum.

Greater stamina, concentration and coordination are

required of those in the intermediate class.

The student is taught to become proficient in designated

“forms” resembling a graceful ballet.

Within these dance-like movements are various defensive and

offensive combinations amalgamated into fluid and continuous sequences.

The forms become more complex and contain highly skilled techniques

that require greater balance and agility.

With detailed training, the student learns to defend himself

against a club, knife or gun. Handling

three or more attackers then becomes an achievable task.

A student considered competent by their instructor is

placed in the advanced class. Again

they are taught higher skills along with the theory and philosophy.

Now their ability is put to an actual test.

They are often asked to spar with fellow students and are required

to stop their blows just prior to contact.

Precision, economy of motion and accuracy become a normal and

integral part of their reflexes. Thus

a serious student discovers that the perfection of Kenpo can be a lifetime

endeavor.

Theory—Philosophy

One cannot realize the deadliness, speed and incredible

power of Kenpo Jiu-Jitsu without witnessing an actual demonstration.

Utilizing principles of physics and leverage, the Kenpo

practitioner is able to strike a penetrating blow to a small vital target

with whip-like speed. After

learning to return a blow at a greater speed than delivered it is

improbable that an adversary could grab the striking hand or foot.

By learning combinations, the Kenpo student makes it extremely

difficult for an opponent to block all of their blows.

Using correct breath control, all of the person’s strength is

released at the moment of impact. An

expert in Kenpo Jiu-Jitsu can easily split a stack of one-inch boards with

the bare knuckles or shatter solid bricks with the “knife-edge” of

their hand.

However, the Kenpo practitioner is basically passive.

The true philosophy of Kenpo is embodied in its creed.

Because of their accomplishments, the standards by which they live

dictates that the student of Kenpo does not seek trouble; nevertheless,

they expect it and are prepared. By

exercising control a person proficient in Kenpo Karate need not

permanently injure an aggressor, but merely render them incapable of

attack. With confidence in

their abilities, fear is banished and trouble avoided.

The ultimate goal of the Kenpo practitioner is one of humility and

restraint.

Conscientious students inevitably qualify for promotion

and are judged according to specific Kenpo criteria.

In time, one’s performance and ability will correspond to one of

several proficiency levels maintained by the school.

These levels are distinguished by a graded belt

system.

Advancement is dependant upon the student’s own efforts.

Many factors are considered for advancement, including an analysis

of the prospect’s character.

The color of the belts consists of white (for

beginners), brown (more advanced) and black (highly skilled).

There are varying degrees within each category; for example the

yellow, orange, purple, blue and green belts are representative of the

degrees, or “Kyu” (steps) of white.

Belts

awarded by other schools are not honored, as the requirements and

curriculum vary greatly from each style and system to another, so there is

no comparison possible.